There are two factors that could greatly increase the potential for reuse of the WDL content, but that are not taken advantage of by all contributors to the project. The first is consistent Creative Commons licensing. Permission for reuse of images is not consistent throughout the project, but varies by contributor and sometimes even by item. This makes it difficult for anyone to use the WDL materials to build new content, even content that is consistent with its educational mission. In fact, even though some content (such as from the Library of Congress) is in the public domain and is marked as having “No known restrictions on publication,” it is so difficult for the user to trace from the WDL item back to the original item on an external website, and to decipher the rights statement to decide whether it is open for reuse or not, that many likely will not even try.

The second factor is linked open data (LOD), data that is openly published on the web and links to other different sources of data. Such links help to represent relationships between entities, such as linking a digitized artwork to another site with more information about the artist, or to more information about the region or time period in which the work was created. Such links would better support the WDL’s educational mission and make the metadata far more reusable. There are several different ways that the WDL could do this, such as publishing the metadata for the WDL objects online as Resource Description Framework (RDF) files, or even by including certain defined metadata attributes (in a format called RDFa) in the HTML for each item page. The closest thing that the WDL seems to have done to this, so far, is to expose the standard metadata on all of the item pages using schema.org microdata formats in HTML. Also, the WDL could make data available using an Application Programming Interface (API), a specification that allows different software systems to communicate with each other, as the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) and Europeana have done. If the WDL information was made available as a machine readable dataset, it would be open to a wide new range of analysis, allowing users to take advantage of machine processing, perhaps to discover unexpected connections between objects around the world. Related to this, it is not clear how much attention the WDL team has paid to search engine optimization. The general public will only find and reuse WDL content if it turns up near the top of the results in popular search engines. Microdata formats for existing metadata will help with this, but more attention could also be paid to the use of related keywords in the entries.

A recent initiative on Wikipedia highlights some of the successes and some of the challenges of WDL content with regards to reuse. The Wikipedia World Digital Library Project is a part of the GLAM-Wiki initiative, connecting Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums with Wikipedia. The goal of the project is to “Improve Wikipedia in any language utilizing the World Digital Library – with special focus on Arabic, English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian and Chinese” (“Wikipedia:GLAM/World Digital Library/Outcomes/Todo,” n.d.).

In the success category, the metadata shared on the item pages using microdata formats has allowed for the creation of an “automatic citation template,” so that a Wikipedia author can merely enter the item number of the WDL item, using the format {{cite wdl|1}}, and a citation will be automatically generated, including creator, date, title, place of publication, and a link to the item page on the WDL (Wikipedia talk:GLAM/World Digital Library, n.d., Citation template). This tool definitely makes it easier to reuse the WDL content on Wikipedia, and it also points to the future creation of even more robust tools for other applications. Furthermore, the Outcomes page for the Wikipedia project shows that since this project launched in May 2013, 52 new articles have been created in English, 13 in Simple English, 5 in Nahuatl, one in Old Saxon, and one in Welsh (“Wikipedia:GLAM/World Digital Library/Outcomes,” n.d.). Also, over 300 existing articles have been expanded, cited, or improved, in 41 different languages.

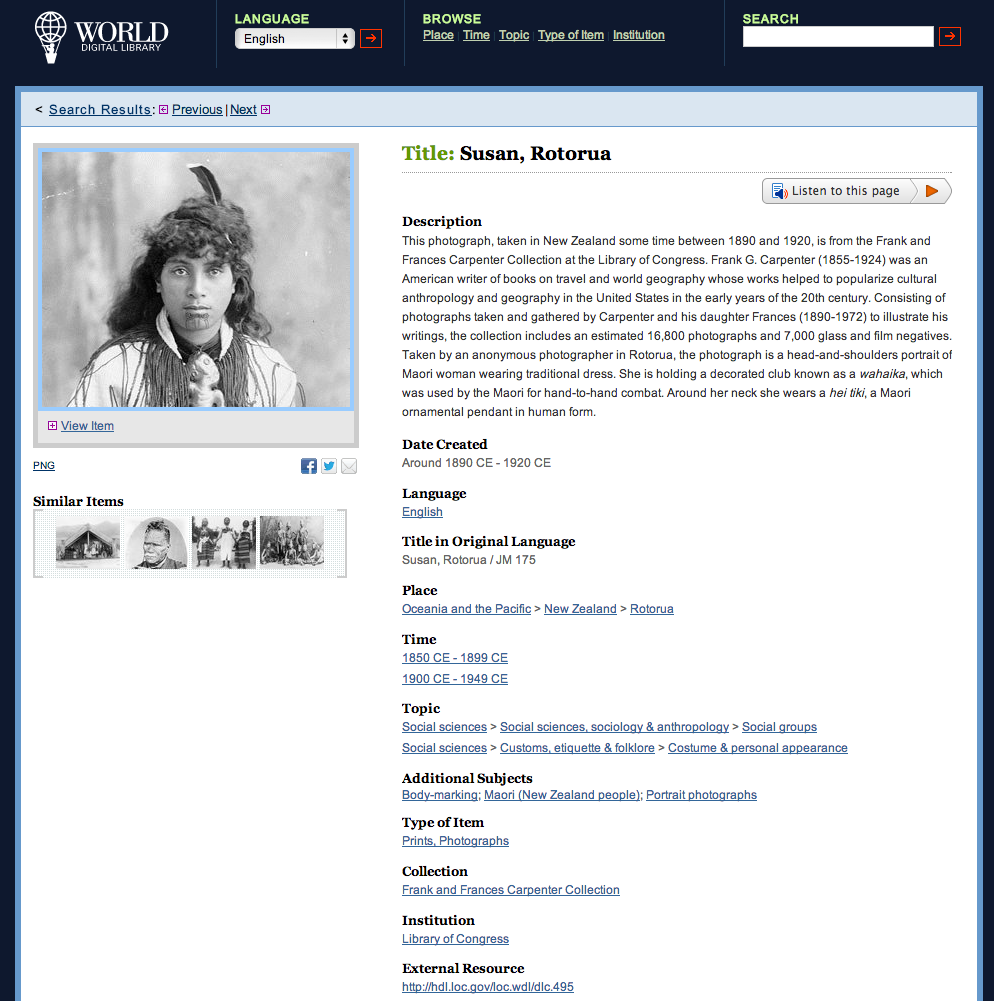

In the challenges category, Wikipedia user “groupuscule” has expressed concerns for the Wikipedia/WDL project with regards to “undue promotion” of the WDL, the question of whether the WDL can be trusted as a source, Eurocentric bias, other possible biases based on the for-profit funders of the project, and a frustration that the images from the WDL haven’t been uploaded to Wikimedia Commons Commons (Wikipedia talk:GLAM/World Digital Library, n.d., Certain troubling issues, with suggestions for positive changes). These concerns are echoed in other user comments throughout the discussion page about the project. User “Stuartyeates” even goes so far as to point out the differences between a WDL page for a photograph from New Zealand (but held at the Library of Congress), and a page for another version of the same photograph at New Zealand’s national museum, Te Papa (Wikipedia talk:GLAM/World Digital Library, n.d., Suggestion for improvement of World Digital Library). The latter includes more specific metadata about the item: “Portrait of a young Maori woman with a feather in her long hair, wearing a large tiki and holding a carved flat greenstone club. She is dressed in a wraparound cloak with tassels, a moko has been added (inked) onto the print image” (Martin, Carpenter, & Carpenter, circa 1890). However, the record for the former, seen in Figure 8, is more focused on information about the American Collection it is a part of.

Figure 8. A screenshot from the World Digital Library, showing a photograph of a Māori woman, from the collection of the Library of Congress. From Carpenter, F. & Carpenter, F. (Circa 1890 CE-1920 CE). Susan, Rotorua/JM 175. [Photographic print of a Maori woman in Rotorua, New Zealand]. World Digital Library (Digital ID: cph 3c12688). Library of Congress, Washington D.C. Retrieved from http://www.wdl.org/en/item/495/

It is also important to point out the notable absences from the languages included so far in the initiative: after the large number of English entries, there are a handful of entries in Gan Chinese and in Arabic, but most of the rest seem to be European, and none appear to be from African languages (“Wikipedia:GLAM/World Digital Library/Outcomes,” n.d.). This points to one of the main disconnects of the WDL: so far, reuse of the content may be serving a mission of increasing understanding of world cultures for First World/western audiences, but there does not appear to be any widespread evidence of its success in reaching audiences in developing countries. The basic tenet of the World Digital Library, to “make it possible to discover, study, and enjoy cultural treasures from around the world” indicates the inclusive proposal of the project. However, when one compares the number of entries on the site from Africa (273), Oceania and the Pacific (40), Southeast Asia (76), with those of Europe (3140) we see that total world heritage is not fairly represented. It serves the user well to examine what those political, historical, and economic factors are that shape the cultural heritage landscape in these developing areas, and the relationships between these regions, to help to explain why these areas are so underrepresented, and how they might be better included.

In order for items to be included into the WDL, they must be digital. As stated in the WDL background, the WDL has worked with UNESCO in supporting the creation of digital conversion centers in the developing world. Together with the Library of Congress centers have been established in Brazil, Egypt, Iraq and Russia and these centers have been integral in providing content to the WDL. Why are there not more of these centers in Africa?

In her 1995 article, Margaret Hedstrom describes two perspectives important to the consideration of digital preservation programs: that of the perspective of the libraries and other custodians responsible for their preservation, maintenance, and distribution, and that of the perspective of the users of the digital materials (Kalusopa, 2009). In Africa, these concerns both suffer from a lack of infrastructure and resources.