Who decides what content is included in the WDL? The intentions of the WDL are inclusive, and the website (WDL, n.d., Frequently Asked Questions, question 8) indicates that

“Any library, museum, archive or other cultural institution that has interesting historical and cultural content may participate.”

However, it’s a little more complicated than that. Section 2.03 of the WDL charter indicates that,

“Applicants to become WDL Contributors must complete and submit an official application to the Project Manager, describing the content they wish to contribute and its significance, or specifying other contributions they intend to make to the WDL. The Project Manager shall evaluate each application and recommend to the Executive Council whether to approve or deny the application” (WDL, n.d., World Digital Library Charter).

Many of the questions on the application are technical in nature, and it is clear that institutions that do not have existing technical infrastructure would have a difficult time participating in the project (WDL, n.d., WDL New Partner Profile).

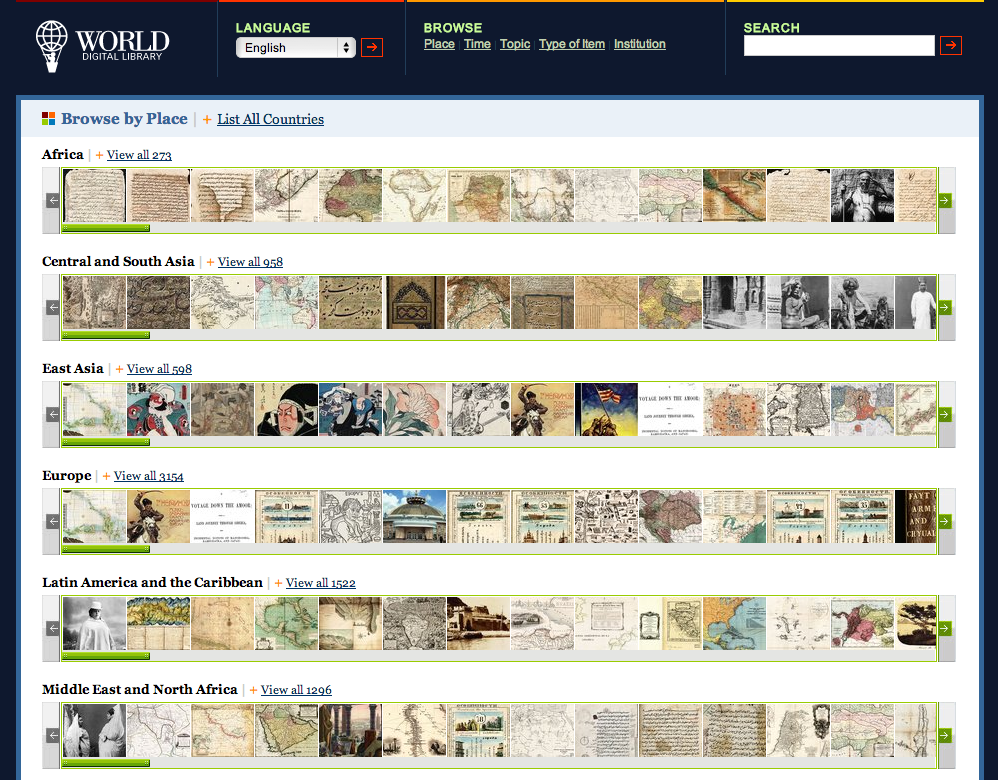

Institutions with existing technical infrastructure have led the way in this project, and though the project’s goal is to share “sources for understanding the history of humanity” (Content Selection Working Group, 2009), this has resulted in an unbalanced representation. As shown in Figure 4, you can conveniently browse the entire WDL collection by Place, Time, Topic, Type of Item, or Institution, and the sub-categories in each transparently indicate their quantity of contents, as shown in Figure 5. Europe leads the Places, 1900-1949 leads the Times, History and Geography lead the Topics, Prints and Photographs lead the Types of Item, and the Library of Congress leads the Institutions.

Figure 4. A screenshot from the World Digital Library, showing the features to choose from 7 languages, to browse by Place, Time, Topic, Type of Item, or Institution, and to choose from the map or narrow the timeline to narrow browsing options. From World Digital Library. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved from http://www.wdl.org/en/ Figure 5. A screenshot of the World Digital Library, showing a portion of the page to browse the library by place. From World Digital Library. (n.d.). Browse by Place. Retrieved from http://www.wdl.org/en/place/

To better include world cultures that are less document-centric, the WDL will need to expand to include representations of three dimensional artifacts. Their inclusion in the future was discussed in 2009, and they intend to experiment with a collection of 3D materials at some point (Content Selection Working Group, 2009). However, it is important to remember that this project is still fairly young as libraries go, even if at eight years it feels old for a web project: James Billington, US Librarian of Congress, first proposed the project to UNESCO in 2005 (WDL, n.d., Background).

Luckily, the WDL appears interested in outreach to expand the number of participating institutions for underrepresented categories, involving training both in digitization and in item description. For example, in 2012, the WDL provided training for technical staff members of contributing libraries in the Arab Peninsula region, hosted in Doha, Qatar (see Figure 6). Individual participating institutions will need both qualified staff and quality equipment to meet the standards of the WDL. High resolution images are needed for the content to be reusable for serious applications, such as in education, but higher quality means more resources, including labor, better equipment, and more storage, all of which increase the expense of the project.

Figure 6. A screenshot of from the World Digital Library project website, showing a list of resources from a workshop held in Doha, Qatar in February 2012. From World Digital Library. (n.d.). Arab Peninsula Regional Group Workshop on Technical Skills and Standards. Retrieved from http://project.wdl.org/arab_peninsula/workshop2012/ar/index_ar.html

Outreach, training, and equipment will be key to the future of this project, as the importance of technical infrastructure cannot be downplayed. For cultural heritage information to be efficiently reusable as public sector information, it has to be formatted following shared professional standards. If the information about each object had to be manually entered from scratch each time it was reused, the time and labor involved would be prohibitive, and few materials would be prioritized for such reuse. Digital technologies allow for the reuse of materials at a much larger scale, by capitalizing on bulk imports and exports, and on search engine technologies that make unique materials discoverable in large global collections. The information about each cultural heritage object is known as its metadata. When metadata follows internationally recognized standards, it improves its interoperability, meaning that it becomes possible to share cultural heritage objects with a global audience, in a variety of different systems.